Feedback from students, faculty and staff has resulted in a different approach to this year’s Martin Luther King Jr. Day observance.

The hope? To engage more deliberately with the Notre Dame community and inspire a renewed personal and communal commitment among faculty, staff and students to help make the University a more welcoming place.

- Related story: MLK Day — A time for reflection

“We have an obligation at Notre Dame to participate in and learn from the ongoing national and even global conversation on diversity and inclusion,” said Notre Dame President Rev. John I. Jenkins, C.S.C. “Our ongoing dialogue about what it means to be the kind of community we strive to be at Notre Dame and the ways that we, individually and collectively, can be a force for good in the world, is critical.”

But engaging in such conversations, even when difficult, is not new to Notre Dame.

From the turbulent civil rights movement of the 1950s and ’60s to today’s efforts to advance justice and human dignity around the world, the University’s commitment to human rights has been inextricably linked to social teachings of the Catholic Church.

1957 >> Father Hesburgh and the Civil Rights Commission

Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., second from

left, with President Dwight D. Eisenhower, center,

was present for the birth of the Civil Rights

Commission in 1957.

From the exhausting fact-finding missions to the final deliberations over wording, former Notre Dame President Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., was a principal architect of the Civil Rights Act. He served on the U.S. Civil Rights Commission from its inception in 1957 until 1972, when President Richard Nixon replaced him after he criticized that administration’s civil rights record.

Father Hesburgh held 16 presidential appointments over the years that involved him in virtually all major social issues — civil rights, peaceful uses of atomic energy, campus unrest, treatment of Vietnam draft evaders, and Third World development and immigration reform, to name only a few.

When President Barack Obama spoke at Notre Dame in 2009, he acknowledged the central role the Holy Cross priest, awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 1999, had played in this chapter of American history.

For more about Fr. Hesburgh’s extraordinary life, visit hesburgh.nd.edu.

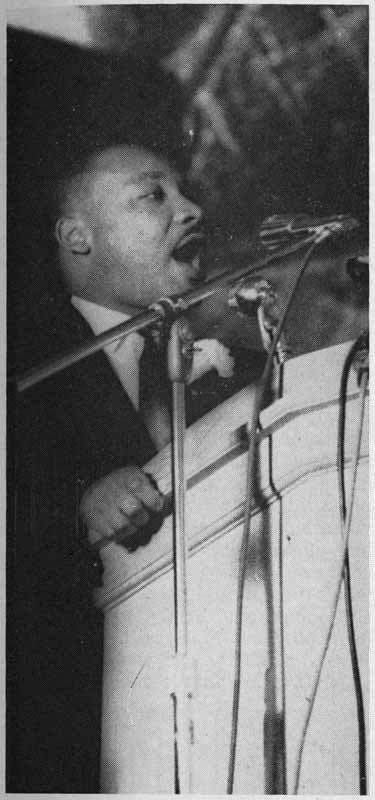

1963 >> King speaks at Notre Dame

In the fall of 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. spoke at Notre Dame’s Stepan Center during an event organized by the South Bend Citizens’ Civic Planning Committee. During his speech, King campaigned for strong civil rights legislation and encouraged nonviolent direct action as a means of protest.

In an article for Scholastic magazine, Richard Weirich wrote of the event:

[King said,] “The world has shrunk to a neighborhood — now we must make it a brotherhood or we will die together as fools.” He reflected upon his trip to India, and the pathetic conditions of the masses there, and commented that “whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly. No man is an island.” King said that we will never be a great nation, and that the world would never be a great world, until we get rid of the idea that there are superior and inferior races. …

The challenge is to rise up and see that “racial segregation is morally wrong and sinful.” (It is sinful in both the North and the South.) “It is a cancer in the body politic which must be removed for moral health.” Segregation is wrong because “it is based on human laws in conflict with the divine. Time will not work the problem out, as has been shown over the last 100 years.” The “people of ill will have used time more effectively than those of good will.” We must help time — “the time is always right to do right.” ...

King’s statement of the role of God in the whole affair sums up his philosophy. He believes in a personal God working with and through man to achieve His ends. But this God has given man a free will, and will not change the social situation without man working.

1965 >> Father Cavanaugh on the front lines in Selma

Rev. John J. Cavanaugh, C.S.C., former

president of Notre Dame, is confronted by

(right) J. Wilson Baker, Selma director of

public safety, on March 12, 1965, in Selma, Alabama.

Perhaps a lesser-known story of a Notre Dame president’s involvement with the civil rights movement was recounted last year in Notre Dame Magazine by editor Kerry Temple.

In “Letter from Campus: The priest at Selma,” Temple writes of Rev. John J. Cavanaugh, C.S.C., predecessor to Father Hesburgh, who stood at the head of a line of marchers in Selma, Alabama, in March 1965. The group was peacefully protesting for African American voting rights but met resistance along the way.

A portion of the article is reprinted here:

This band of activists was intent on a peaceful protest but determined to help Southern blacks gain voting rights still deprived them despite the 1964 U.S. Civil Rights Act.

At the head of line was a Holy Cross priest. Notre Dame’s 14th president. The man who in 1952 had turned the presidency over to Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C.

Father John J. Cavanaugh, C.S.C., was 66 on this day in Selma when his path was blocked by a public safety officer who reportedly said he could not believe a man of God would march without a permit. “We may talk cross while excited,” Cavanaugh replied, “but we ask you to pray for us, that you may see our cause.”

“I cannot understand this violence, sir,” said J. Wilson Baker, Selma’s director of public safety, to which Cavanaugh responded, “We don’t look for violence. We believe in justice for all. We ask the blessings of God, of the Father, the Son and Holy Ghost on all of you.”

To read this article in its entirety, check out the Summer 2015 print edition of ND Magazine or visit magazine.nd.edu.

1973 >> The Center for Civil and Human Rights

The Center for Civil and Human Rights was founded in 1973 to ensure that Notre Dame remained at the forefront of the fight for civil and human rights.

Through education, the center aspires to equip human rights lawyers and other students to become champions of human rights in every corner of the world. Through research, the center aims to raise awareness of particular forms of oppression among activists, officials, scholars and students in order that they may promote human rights more effectively.

In all of its efforts, the center stands in solidarity with the oppressed, the afflicted and the vulnerable and seeks to secure their human rights and the conditions for their flourishing.

Father Hesburgh and President Eisenhower photo from the Associated Press. Martin Luther King Jr. photo courtesy of University of Notre Dame Archives. Father Cavanaugh's photo courtesy of the Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Marquette University Libraries.