Barry McCarron

Barry McCarron

Barry McCarron earned his Ph.D. in history from Georgetown University and is an assistant professor of history and faculty fellow in Irish Studies at New York University. He received a 2017 Research Travel Grant from the Cushwa Center to explore sources in the Notre Dame Archives relevant to his forthcoming book, The Global Irish and Chinese: Empire, Exclusion, and Foreign Relations in the Long Nineteenth Century. This is the first study to examine relations between the Irish and Chinese in the Americas, the British Empire, and China in this period. McCarron’s research at Notre Dame focused on the question of the stance of Irish Americans and the Catholic Church toward Chinese immigrants and the anti-Chinese movement that culminated in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. We caught up with McCarron in June 2017 during his research visit on campus.

In your grant application, you point out that while a great deal of attention has been given to Irish American–African American dynamics, almost nothing has ever been said about the Irish and the Chinese. Why do you think this topic has been so understudied?

There are journal articles and book chapters that examine the Irish and Chinese interethnic dynamic, although most of these are local studies or focus on a particular topic. “The Global Irish and Chinese” is the first study of relations between the Irish and Chinese from global, comparative, and transnational perspectives. It explores topics ranging from migration, race, and citizenship to nativism, empire-building, and foreign relations. A project of this scope, which involves multinational and multilingual primary research, presents some challenges. Archival research in several countries is an expensive and time-consuming process and examining the Chinese stance towards the Irish, an understudied area but necessary for a balanced treatment of Sino-Irish relations, requires Chinese language proficiency. The literature on the Irish diaspora and the Chinese diaspora is voluminous but there are few historians who have a research agenda centered on both of these fields and who bring Irish and Chinese history into conversation with one another.

What collections have you been using at Notre Dame? What have you found most useful?

My research has centered on the papers of Irish American Catholic clergy, the records of Irish American newspaper editors, and several Catholic newspapers with a mostly Irish American audience. The newspapers have been most useful because they contain numerous editorials and widespread coverage of the anti-Chinese movement in the United States. Also, the staff at Rare Books and Special Collections helped me locate and duplicate original Catholic newspaper images of the Chinese that I plan to use in my book project.

Are clergy and newspaper editors basically in agreement or do you see differences in their stances?

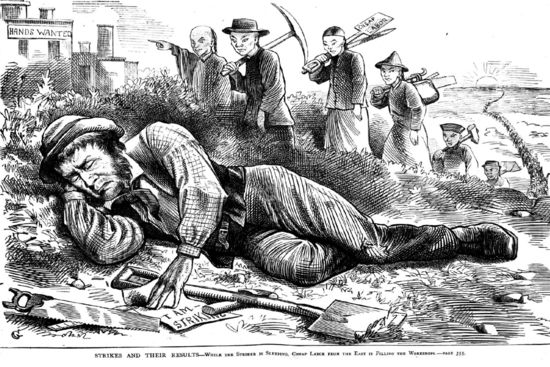

Irish American Catholic clergy and newspaper editors, or at least those who expressed views on the “Chinese question” in the primary sources I have consulted, generally supported Chinese exclusion and immigration restriction. Common themes appear in their anti-Chinese rhetoric, most notably Chinese immigrants supplanting or undermining the wages of Irish Americans. They typically describe the Chinese as racially inferior and unassimilable. Some of the most vitriolic attacks on the Chinese emanated from Catholic Irish American newspapers including official organs of Catholic dioceses. These attacks appeared in both written text and cartoon format. Several cartoons in Irish Catholic newspapers such as one in McGee’s Illustrated Weekly (New York) depict an endless stream of Chinese “cheap labor” invading the United States from the East to take the jobs of Irish American workers.

Were there Catholics among the Chinese immigrants? How did religious difference affect the tensions between the Irish and Chinese?

Chinese Americans did not convert to Catholicism in appreciable numbers until the early 20th century. Irish American politicians, newspaper editors, labor leaders, and Catholic clergy, in their justifications for Chinese immigration restriction, frequently characterized the Chinese as immoral heathens, pagans, and barbarians unfit for American citizenship and a threat to American values and institutions. This religiously-infused Sinophobia exacerbated conflict between Irish and Chinese workers. Interestingly, many Chinese Americans challenged their Irish opponents by aligning themselves with Protestant missionaries who were sympathetic to their plight and openly hostile towards Irish Catholics.

This is a project that looks at the British Empire and the United States. Can you briefly sketch the similarities and differences you see between Catholic responses in the United States and in the British territories?

The dominant pattern in relations between the Chinese and Catholic Irish in the United States and the British Empire’s white settler colonies in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and South Africa was one of racial conflict and economic competition. However, there were a few Irish who transcended this racial divide in the second half of the 19th century. One prominent example was the Irish-born Archbishop of Sydney, Patrick Francis Moran, who was one of the foremost champions of Chinese racial equality in colonial Australia. I have yet to discover Irish American Catholic clergy who shared Moran’s commitment to racial equality for Chinese immigrants.

Image: McGee’s Illustrated Weekly, April 24, 1880, p. 364. Original caption reads: “Strikes and their results—While the striker is sleeping, cheap labor from the East is filling the workshops.”

Originally published by at cushwa.nd.edu on October 24, 2017.