I sit beside a large man who is sobbing and wearing a cowboy hat.

In the front of the room is a hollow, emerald green statue of Lady Liberty about as tall as I am. I’m holding one of those miniature American flags — I accepted mine begrudgingly when we entered the room, but I see other people waving theirs with fervor. I know this flag. I have pledged allegiance to it every morning from first through eighth grade. I’ve worn its colors every Fourth of July and memorized the states that each star represents, as well as their capitals.

But here I am sitting in this room, expected to act as though it is the first time I have ever seen red, white and blue.

This is my American citizenship ceremony. I am 14 years old and irritated that I have to miss a day of school to be “welcomed” into a country that I have already been living in for 11 years. A thousand questions pop into my mind. Is America not my home? Am I still considered an outsider? If America isn’t home, what is? I was born in the Philippines, but I have no memory of being there.

My identity is nomadic. A Filipino in America; an American in the Philippines. No matter where I go, I exist in the middle of a Venn diagram, a jigsaw piece that does not fit in either puzzle.

Next to me, the cowboy hat bobs up and down even faster. The large man beneath has dissolved into more violent sobs. President Obama has just come onto the screen.

As a little girl going to school in America for the first time, I was bombarded with more English than I had ever heard before. I was self-conscious about sounding different from other children, about having an accent, though at that time I was unaware there was even a word for this. I simply saw it as an imperfection whenever I mispronounced a word.

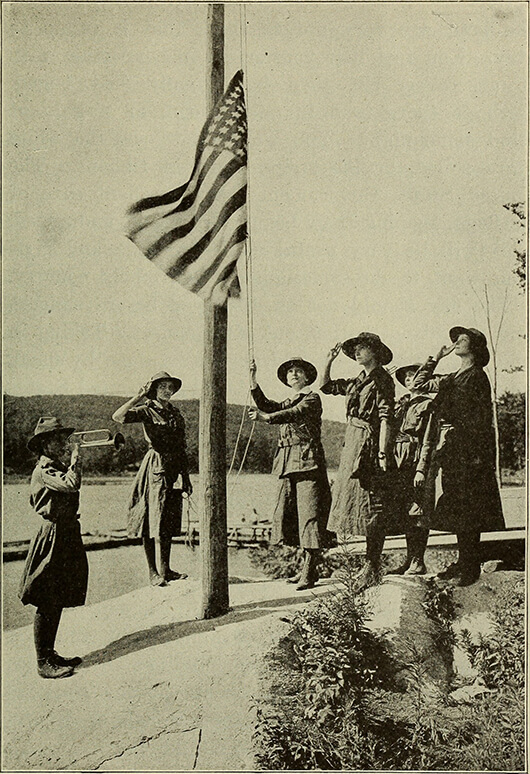

Image from What to Do for Uncle Sam: A First Book of Citizenship (1918).

Image from What to Do for Uncle Sam: A First Book of Citizenship (1918).

At home, my parents attempted to preserve our Filipino culture. They spoke Tagalog to me and insisted I reply in it as well. But first-grade me resisted and I responded every time in English. At first they scolded me, but eventually my parents gave up and conversations in our house became hybrids of English and Tagalog, or what they called “Taglish.”

Cowboy Hat Man waves his miniature flag. Obama is done speaking. In the background, I can hear the first notes of “God Bless the U.S.A.” by country singer Lee Greenwood. I brace myself for what I know are more sobs to come.

Back in elementary school, mom would pack me Filipino food for lunch — usually some combination of meat and rice. I remembered not thinking anything of it the first day, opening my lunch and grabbing a fork, when suddenly someone looked over and asked what I was eating. I explained it to them and then looked at their lunches. I remember seeing the table littered with Ziploc baggies that held either peanut butter and jelly or ham and cheese sandwiches. I got so tired of my lunch becoming an exhibit, that I started buying my lunches even though mom kept packing me one. When I came home with an untouched lunch, mom grew worried and asked me why I wasn’t eating. I didn’t have the heart to tell her. I felt guilty every time.

Cowboy Hat Man puts his arm around me, trapping me in a forced sway as Lee Greenwood sings on.

During my freshman year at college, my friends and I attended a party that was no different from any other except for one distinctive conversation. Everything was going fine with this guy — we traded normal questions such as “What’s your major?” or “What dorm are you in?” when suddenly he asks one that I don’t know how to answer.

“So, what are you?”

My cheeks flushed red. I was shocked, embarrassed and most of all angry. What resulted from this hodgepodge of emotions were the two words I knew he was waiting for.

“I’m Filipino.”

Feelings of disappointment flowed into my concoction of emotions. Why did I let myself down like that? Why didn’t I just explain I was American?

More important, was I angry because he asked such an inappropriate question or because I didn’t know the answer?

In the end, I decided explaining these struggles with my cultural identity to an already nervous college boy with a warm beer in his hand made for less than appropriate party talk and an even bigger waste of my time. I turned on my heels and walked away, but his question has bothered me since.

Cowboy Hat Man releases me, and we sit down. Up front, an employee of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security prepares the certificates of citizenship and begins calling people up one by one.

I remember the exact moment I embraced the duality of my cultural identity because it happened not long ago. It was the summer after my freshman year, and I was involved in a Summer Service Learning Program as a casework intern for a non-profit immigration office in Dallas. My duties included studying immigration law and helping immigrants determine their eligibility for citizenship or immigration relief. One day, instead of working on these cases my supervisor sent me to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services Office in Irving, Texas, to attend a lecture on immigration policy.

After I passed through security, we entered a room with glass walls. I sat down and tried to learn about the requirements for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals but I wasn’t paying very close attention and my eyes roamed until they locked onto a hollow, emerald green statue of Lady Liberty standing in the corner.

Suddenly, I couldn’t hear the lecturer anymore. I realized I was in the room of my citizenship ceremony, but this time my goal was learning how to help others build lives in America just as my parents, brother and I had. Five years earlier, I had been one of those immigrants and I took my citizenship for granted. I was also a dependent, which meant my parents went through the entire process of applying and taking the American history test while my brother and I simply piggybacked off their results. I had been unaware of the complexities of applying for citizenship or legal residency in the United States and reduced the ceremony to an inconvenience and an absence at school. Now I was standing in the same room while doing work that enabled me to see for myself the disappointment on people’s faces when their applications were rejected. I felt sick.

Cowboy Hat Man walks back to his seat, holding his certificate in one hand and waving his flag in the other. Tears stain his face, but his smile exudes serenity. The sobs have stopped.

“Selena Ponio!” the Citizenship and Immigration Services employee calls out. My name is followed by a smattering of applause as I walk up to get my certificate.

Today, I am proud. I see the duality of my cultural identity not as a detriment, but a blessing. I feel nothing but pride when I share some of my family’s traditions with my friends and talk about how much I miss the Filipino food my dad cooks at home. I laugh when I go back home to the Philippines and my cousins poke fun, calling me “the girl with the American accent.” I feel nothing but gratitude towards my parents for helping me retain Tagalog, especially when I call my grandparents and talk to them in the language they are most comfortable with.

I am proud to exist in the intersection of this Venn diagram, experiencing two cultures that have both contributed to the person I am today. So, what am I? I am the daughter of immigrants, an American citizen, a Filipino woman. When I finally realized being an American and a Filipino were not combative identities, I felt like I fit in the puzzle.

I hold my certificate up, stand by Lady Liberty and smile for a picture, then return to my seat. Cowboy Hat Man turns to me, pats me on the back and smiles.

“Aren’t we so lucky?” he says.

Selena Ponio is a senior in international economics and the Gallivan Program in Journalism, Ethics and Democracy. She is currently interning at 60 Minutes for CBS News in New York City.

Originally published by at magazine.nd.edu on July 13, 2017.