By Benjamin J. Wetzel

The Seminar in American Religion convened on March 24, 2018, to discuss Judith Weisenfeld’s prize-winning book, New World A-Coming: Black Religion and Racial Identity during the Great Migration (NYU Press, 2016). About 80 people attended the seminar, which was moderated by Thomas Kselman, professor emeritus of history at the University of Notre Dame.

Weisenfeld is the Agate Brown and George L. Collord Professor in the department of religion at Princeton University and has written several other major studies analyzing African American religious experiences in the early 20th century. The seminar’s commentators included Paul Harvey, distinguished professor and presidential teaching scholar in the department of history at the University of Colorado, Colorado Springs; and Jennifer Jones, assistant professor of sociology at the University of Notre Dame.

In 2017, New World A-Coming received the Albert J. Raboteau Book Prize for the best book in Africana religions. Raboteau (Weisenfeld’s colleague at Princeton, now emeritus), while studying most facets of African American religions, tended to focus on Protestant and Catholic Christianity. New World A-Coming, by contrast, highlights smaller religious groups like the Nation of Islam, the Moorish Science Temple, the Ethiopian Hebrew congregations, and the Peace Mission of Father Divine. These movements merged religious and racial identity, offered stark contrasts to mainstream Christianity, provided hope and vision to their adherents, and flourished in the urban north during the Great Migration even while they remained on the margins of American religious life as a whole.

Jennifer Jones

Jennifer Jones

Jennifer Jones offered the first round of seminar comments. She praised the “incredibly engrossing” book for its approach to racial questions and for its illumination of the history behind these religious movements. Jones, an expert on racial formation, explained how American society in this period structured race so that African Americans remained consistently at the bottom. Yet, she pointed out, Weisenfeld’s book shows how blacks themselves could forge their own notions of race and evoke history, real or imagined, to buttress their ideas about religion and ethnicity. Jones also noted links between the project of the characters in New World A-Coming and the contemporary philosophies of Afro-futurism and Afro-pessimism, which also re-conceive the pasts and potential futures of Afro-descended people. Finally, Jones called attention to the prejudice Weisenfeld’s groups faced from many northern black leaders as well as from governmental authorities. She concluded by reflecting on the extent to which their efforts at self-definition did or did not lead to concrete changes in the political and social realm.

Paul Harvey

Paul Harvey

Paul Harvey’s response followed. He called the book a “landmark” in African American religious history and focused his comments on the study’s historiographical contribution to the field. He praised Weisenfeld’s use of source material, particularly FBI files, census records, and information obtained from Ancestry.com. Harvey noted that, in his view, many of the best recent books on African American religious history featured non-Christians as the leading actors, suggesting that the idea of “religious construction” is particularly compelling to contemporary scholars. Weisenfeld’s characters, Harvey said, participated not only in constructing new religious movements, but also in re-constructing racial categories. Harvey also concluded by drawing parallels between the Afro-futurist philosophies advocated by the groups in New World A-Coming and those present in the recent popular film Black Panther.

Responding to commentators Jones and Harvey, Judith Weisenfeld explained that she has always been attracted to ordinary people and non-Christian religions and implied that this project represented her core research interests since her days in graduate school. She acknowledged the difficulty in describing her groups, noting that labels like “sects” and “cults” would not do. In the end, she said, “religio-racial movement” best designated the groups’ raison d’etre. Weisenfeld also discussed how these religio-racial movements, despite their unconventional views, desired to gain “official recognition” (from cultural gatekeepers) as legitimate religious groups. While organizations like the Nation of Islam dwelt on the margins of American life, they wanted to break into the mainstream. Finally, Weisenfeld agreed that thinking about her groups in the frame of “Afro-futurism” and “Afro-pessimism” was helpful for understanding how they used the past to envision a more promising future. She referenced the work of 20th-century novelist Octavia Butler, especially her Parable of the Sower (1993), as especially relevant in this regard.

After a short break, the panelists fielded almost a dozen questions from the audience. Suzanna Krivulskaya (Notre Dame) recounted the scandals associated with some of the founders of these alternative religio-racial movements and asked why such stories did not play a more prominent role in Weisenfeld’s narrative. Weisenfeld responded by saying that her main interests lay in what attracted people to these movements rather than what caused some to leave, although she did acknowledge the more negative stories that might be told about the founders of these groups.

Jana Riess (Religion News Service) asked about the “science” in the Moorish Science Temple (MST) and why the MST’s links with New Thought and Christian Science were not better known. Weisenfeld stated that New Thought ideas permeated several of these groups but that the theologies of movements like the MST “have just not been taken seriously.” She said that scholars should focus on more on the “connections and sources” for these groups’ theologies rather than highlighting only the exotic, performative nature of their customs and rituals.

Peter Cajka (Notre Dame) asked the panelists to reflect on how such material might be incorporated in the classroom. Harvey thought New World A-Coming might work well with undergraduates but noted that professors would need to help students distinguish between reacting to the groups’ normative theological claims and dispassionately analyzing the movements’ processes of formation and other empirical issues. Harvey also suggested students would need to be persuaded that the groups are worth studying since their numbers were relatively small.

Laurie Maffly-Kipp (Washington University in St. Louis) wanted to know how studies like Weisenfeld’s might shed light on the broader narratives in American religious history. Weisenfeld expressed hope that the groups in her book might be included in the bigger narratives and reminded the audience that people were sometimes involved in outsider groups and more mainstream groups simultaneously. Jones added that, from a sociological perspective, it is important to remember the particular contexts of racial formation—a point that calls into question the idea of all-encompassing grand narratives.

John McGreevy (Notre Dame) pushed back on Weisenfeld’s claim that her groups caused much soul-searching among mainstream black Christian leaders. He also asked whether it was ever appropriate for historians to use terms like “cult,” “sect,” or “superstition.” To the first point, Weisenfeld maintained that the groups under consideration participated in a broad cultural conversation among African Americans about religion and racial identity and were thus not on the margins in that regard. (Jones reminded the audience that the movements would have been locally prominent even if numerically small on the national scale.) Weisenfeld also held that the term “sect” could be used neutrally but that the terms “cult” and “superstition” were inherently bound up with pejorative connotations and thus should not be used by scholars.

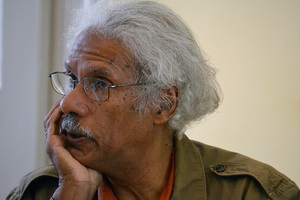

Albert Raboteau

Albert Raboteau

“A history of slavery, disenfranchisement, and discrimination in America made African-Americans feel like aliens in their own land,” Albert Raboteau wrote in “The Black Church: Continuity within Change,” in Fire in the Bones: Reflections on African-American Religious History (1997). “Black Jews and black Muslims,” he continued, “solved the dilemma by embracing their alienation from Christianity and from America” (111). While Raboteau pointed to the stories of non-Christian African Americans in this essay, until now we have not had as insightful a study of these groups as Weisenfeld offers in New World A-Coming. Her work contributes significantly to our understanding of racial formation, African American religion, the urban north, the interwar period, and the relationship between religion and the state. Future scholars will take these themes in new directions, but they will be indebted to the foundations laid in New World A-Coming.

Benjamin Wetzel is a postdoctoral fellow at the Cushwa Center.

Albert Raboteau photo credit: Daniel Silliman, 2012

Originally published by at cushwa.nd.edu on May 31, 2018.