Rebecca McKenna

Rebecca McKenna

At its peak of popularity in the early 1900s, hundreds of thousands of pianos were being manufactured and sold in the United States each year.

But for Rebecca McKenna, the piano’s history is about much more than just manufacturing or marketing — it’s about issues of race, class, and gender at the turn of the 20th century. It’s about transnational trade and the debut of a new genre of music.

McKenna, an assistant professor in the Department of History, is exploring all of these issues for her new book project, with support from a National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship.

“In so many ways, this is new ground for me, because I haven’t done music history before,” McKenna said. “I’m excited for what the story encompasses and what it requires me to bring together to tell it.

“I’m also grateful for this recognition from the NEH. It’s encouraging to learn that people who care about American culture and history see merit in this project, and it allows me the time to begin researching in a much more substantial way.”

“I’m grateful for this recognition from the NEH. It’s encouraging to learn that people who care about American culture and history see merit in this project, and it allows me the time to begin researching in a much more substantial way.”

Unaddressed threads

McKenna’s interest in the project began with a research paper she wrote while pursuing her Ph.D. at Yale University. That project examined the history of Ivoryton, Connecticut, a small, company-built town named for the ivory it received from East Africa and the products manufactured there — including combs, billiard balls, and piano keys.

“I had wanted to do a transnational history project and found this place intriguing,” she said. “I looked at how its built environment was shaped by this transnational exchange and was dependent on slavery, because it was often slave labor that was bringing ivory to the coast of Africa.”

A few years ago, McKenna revisited that paper and realized there was a larger story to be told. As she began looking into the history of the piano, she found there was not a significant body of research on it, especially considering how dominant the instrument was in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

“The existing material tends to focus on its technical development or how savvy American manufacturers innovated forms of mass production and marketed the piano,” she said. “But there are all these interesting threads that weren’t really addressed, including how dependent upon the ivory trade the U.S. piano industry was and how American popular music was driving people to want to buy pianos or learn to play.”

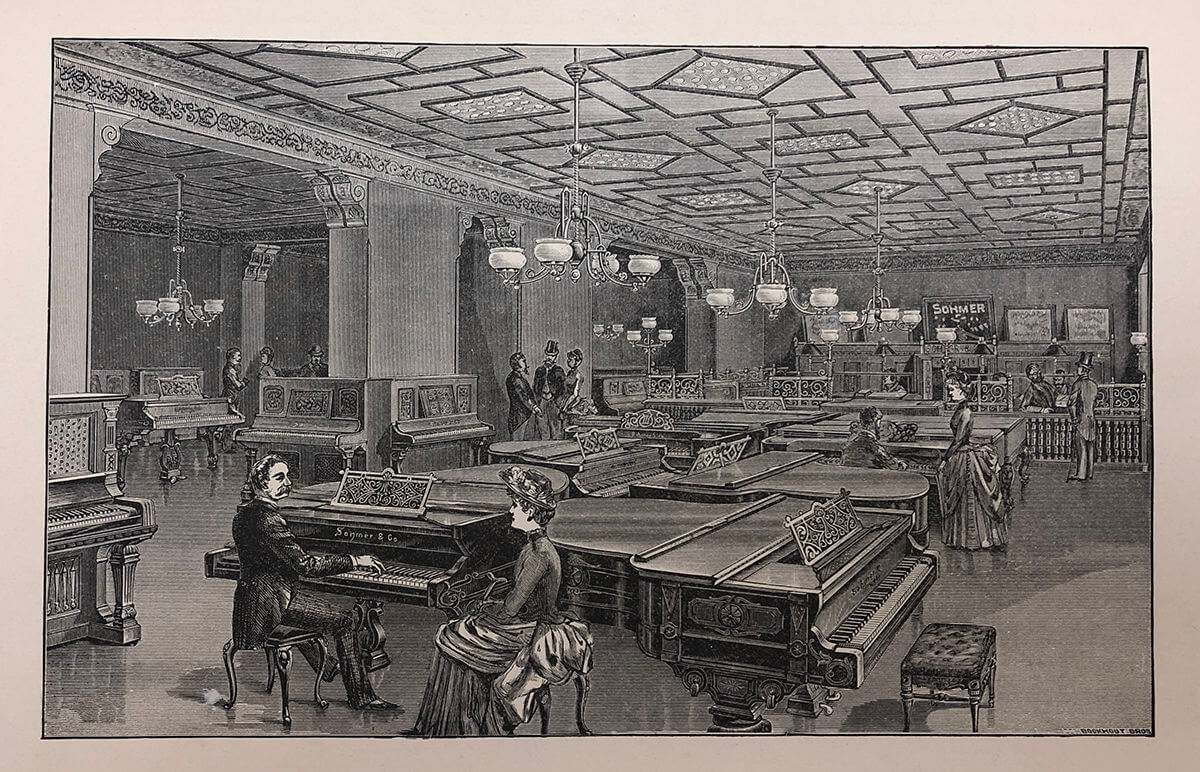

An image McKenna discovered in her research from the Illustrated Catalogue of Sohmer & Co., c. 1888-89. Sohmer & Co. was a New York-based piano manufacturer founded in 1872. This image appears to be of Sohmer’s West 57th Street showroom, where salesmen seem to be demonstrating the virtues of Sohmer pianos to women shoppers.

An image McKenna discovered in her research from the Illustrated Catalogue of Sohmer & Co., c. 1888-89. Sohmer & Co. was a New York-based piano manufacturer founded in 1872. This image appears to be of Sohmer’s West 57th Street showroom, where salesmen seem to be demonstrating the virtues of Sohmer pianos to women shoppers.

A rise and fall

McKenna envisions that the chapters of her book will focus on the places significant to different aspects of piano history — from the Chickering & Sons piano manufacturers and sheet music industry in Boston to the debut of ragtime at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893 to the ivory industry in Zanzibar and, eventually, to the publishers and songwriters of Tin Pan Alley in New York.

Along the way, she will examine larger themes of consumption, empire, gender, and race — as they relate to the piano as a status symbol, primarily for middle-class white Americans.

“One part of the story that needs to be told is about women as consumers and players of pianos and the idea that part of what made you marketable as a wife was that you could play the piano,” McKenna said. “There’s also a racial component — I am trying to get a sense of what makes someone a white, middle-class American at this point in time and the way consumption of certain commodities signals that.”

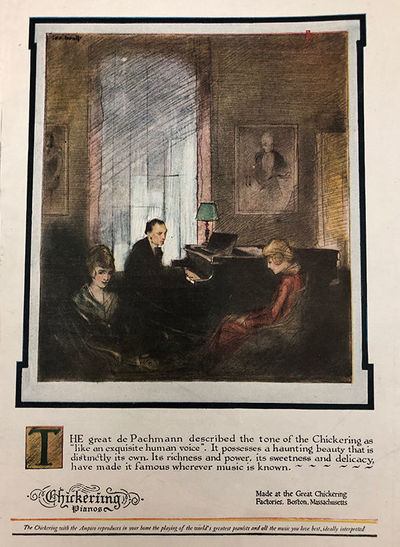

An undated advertisement (probably c. 1910) for a Chickering baby grand piano. Chickering & Sons was the first major manufacturer of pianos in the United States.

An undated advertisement (probably c. 1910) for a Chickering baby grand piano. Chickering & Sons was the first major manufacturer of pianos in the United States.

McKenna plans to explore how demand for the piano was driven both by its role as a status symbol and by the introduction and growing popularity of ragtime — the first genre of sheet music that sold in large quantities, reaching more than $1 million in sales for Scott Joplin’s “Maple Leaf Rag.”

“It’s a rise-and-fall kind of story — ragtime helped to drive the popularity of the piano, but I think it also helped to create a culture that meant the piano was going to be succeeded by new technologies,” she said. “That’s part of what I want to explore and share — how this new African American-produced music is embedded in the politics and history of the instrument.”

Drawing on strengths

This fall, McKenna will be teaching a course on the United States’ Gilded Age and Progressive Era — where her teaching will dovetail with her current research.

“There are many ways I feel the course has helped me discover interesting things about ragtime or about the piano, just as I think the research I’m doing will help fill out the story of that class,” she said. “I can imagine my work on the piano inspiring me to bring in more objects and material culture to get at the dynamics I talk about now in, perhaps, a more abstract way.”

McKenna, who will begin a research leave in January, is grateful for the resources she has at Notre Dame and is looking forward to connecting with colleagues in the Department of Music on aspects of the project relating to music theory and history.

“The University is just incredibly generous in providing funding, which allowed me to do my preliminary research. Without that, it would be very difficult to do this project,” she said. “And there are all these strengths I can draw on across the College, including the incredible scholars in my own department and the Department of Music, as I continue to conceptualize the project and work out parts of it.”

“The University is just incredibly generous in providing funding, which allowed me to do my preliminary research. Without that, it would be very difficult to do this project. And there are all these strengths I can draw on across the College, including the incredible scholars in my own department and the Department of Music.”

Originally published by at al.nd.edu on August 13, 2019.