Carlos Jáuregui

Carlos Jáuregui

Zygmunt Baranski

Zygmunt Baranski

From the beginning, there’s an end in sight.

For students in Notre Dame’s new Ph.D. in Italian and Ph.D. in Spanish programs — each of which launched in 2016 — the focus is on ensuring students complete their dissertations and earn their degrees within five years.

“It’s our defining characteristic,” said Zygmunt Baranski, director of Italian graduate studies and the Notre Dame Professor of Dante and Italian Studies. “Our program is trying to combine the American idea of coursework with the European model of the Ph.D. From their first year, students are working with their advisers on a thesis. It’s not something you only start to do once you finish your coursework.”

As the first new graduate degrees formed since the creation of the College of Arts and Letters’ innovative 5+1 Postdoctoral Fellowship Program, the curriculum and structure have been designed to incentivize and facilitate timely degree completion. Coursework is concentrated in the first two to three years of the program, leaving ample time for each student to pursue a significant work of scholarship.

The programs are attracting high-caliber students from around the world, helping to strengthen a flourishing community of scholars that includes students in successful master’s of arts programs already operating in each area.

“Our Ph.D. is not about the completion of a set of classroom requirements,” said Carlos A. Jáuregui, director of Spanish graduate studies and associate professor of Latin American literature and anthropology. “Our Ph.D. is about the completion of a dissertation — that represents a new and significant contribution to the area of studies, and places the student in the field and in the job market.”

“We want to produce great scholars and great teachers, and we have to prepare them from day one. We want them to be successful and give glory to this University with their publications and their success. And we won’t lose track of that goal.”

— Carlos A. Jáuregui, director of Spanish graduate studies

Great students make great colleagues

Third-year Ph.D. student Lorenzo Dell’Oso traveled to Florence, Italy, this summer as part of his research on the intellectual formation of Dante.

Third-year Ph.D. student Lorenzo Dell’Oso traveled to Florence, Italy, this summer as part of his research on the intellectual formation of Dante.

A native of Pescara, Italy, third-year Ph.D. in Italian student Lorenzo Dell’Oso turned down offers from other schools, including Yale and Johns Hopkins, to remain at Notre Dame after earning his master’s degree in Italian studies here.

He’s found the intellectual environment in the program to be stimulating and exceptionally collegial with an emphasis both on specialization and the exploration of secondary fields of interest. But most importantly, he said, the faculty in the program are exceptional.

“It’s astonishing to have several Dante scholars in the same school — it’s something unique that you don’t find even in Italy,” Dell’Oso said. “Once I decided to become a Dante scholar and a medieval Italian scholar, I didn’t have any other choice than being at Notre Dame.”

His research focuses on the intellectual formation of Dante and how a layman with little access to books went on to write such essential literary masterpieces.

He spent the past summer studying manuscripts in Florence, Bologna, and Rome reading transcripts of 13th-century discussions that occurred in convents between friars and laypeople about theology, philosophy, and literature. Men and women could ask the religious leaders about anything, and the priests often answered by quoting authors or theologians. Thus, while commoners didn’t have direct access to knowledge, they could become cultured through oral dialogue.

“A common view of Dante and other geniuses is that they were able to know everything and understand everything because they had access to thousands of books,” he said. “But these were normal men — men who would have found it difficult to gain access to books. But they weren’t isolated. This is how medieval culture worked.”

The Italian program has placed a special emphasis on developing overseas collaborations, including an exchange program with Cambridge University and opportunities for students to visit universities in Rome while utilizing Notre Dame’s Global Gateway there.

“It helps students broaden their perspective, which can be very important once they start applying for jobs. It’s another feature of our degree that few others can match,” Baranski said. “By having contact with a wide range of academics beyond South Bend, they can be recognized as great students who will make great colleagues in the future.”

“It’s astonishing to have several Dante scholars in the same school — it’s something unique that you don’t find even in Italy. Once I decided to become a Dante scholar and a medieval Italian scholar, I didn’t have any other choice than being at Notre Dame.”

— Lorenzo Dell’Oso, third-year Ph.D. in Italian student

Great scholars and great teachers

The Ph.D. in Spanish program has attracted talented, accomplished students in its first two cohorts, and makes it a priority to support, encourage, and reward research and publications. In the last two years, students in the program have had 11 articles published or accepted for publication in peer-reviewed journals — including eight articles, plus two chapters for collected volumes, accepted in the past year alone.

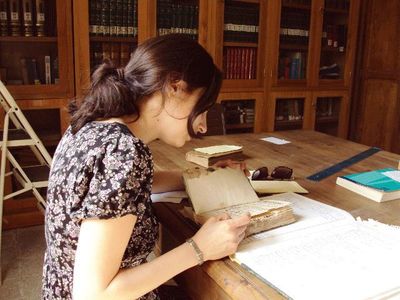

Leonor Taiano Campoverde conducting research at the Biblioteca del S.S. Crocifisso in Cosenza, Italy.

Leonor Taiano Campoverde conducting research at the Biblioteca del S.S. Crocifisso in Cosenza, Italy.

Leonor Taiano Campoverde, a first-year student and presidential fellow, previously earned a Ph.D. in sociology and humanities at the University of Tromsø in Norway and master’s degrees at the University of Rome III and the Pontifical University of Salamanca. Her research on Spanish-Hispanic American culture and literature includes topics in the Spanish colonial period, Hispanic history and identity, and the relationship between art and propaganda.

She has had articles published in Bibliographica Americana, Cuadrivium, and Pucara Journal of Humanities and co-edited Finisterre: In the last place in the world. She is currently working on an edition of the 17th-century work Los infortunios de Alonso Ramírez and a book about the Jorge Majfud novel Crisis.

“After working for many years in subjects connected with Spanish literature and culture, I was very attracted to the program at Notre Dame,” she said. “The tradition of the University, the superb faculty mentorship, and especially their focus on research and research productivity prompted me to apply.”

Second-year student Luis Bravo, a native of Montevideo, Uruguay, has published five books and several articles on the works of Ibero Gutiérrez, a mid-20th-century young writer who became a student martyr after compromising with 68 counterculture rebellions in Latin American.

Bravo has also published works focused on Latin American avant-garde poetry, art and politics, and gender studies, and he is currently the curator research at the I. Gutiérrez Archive at the National Library of Uruguay — work that began when the nation restored its democracy after 12 years of military dictatorship. He also was a 2012 resident in the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa.

Second-year Ph.D. student Luis Bravo has published five books and several articles on the works of Ibero Guitérrez

Second-year Ph.D. student Luis Bravo has published five books and several articles on the works of Ibero Guitérrez

He has extensive teaching and academic experience after 20 years as a professor in the prestigious Pedagogical Institute (Instituto de Profesores “Artigas”), and 15 years at the University of Montevideo, both in Uruguay. He is working on a dissertation that addresses the philosophical, historical, and aesthetic aspects of Gutiérrez’s avant-garde writings.

“I applied for this program because it is one of the most outstanding in the United States — one that focuses on the Ph.D. as a successful writing and defense of a dissertation which, I hope, can contribute to the global studies where literature, human development, and social thought converge,” he said. “It’s an honor and a privilege to be a graduate student among this faculty that includes very well-known professors for their academic work, as well as having at my disposal a vast library containing the best humanistic tradition.”

In addition to offering opportunities for students to travel to conduct and present research, Jáuregui said, the program is also focused on training its Ph.D.s to be quality teachers.

On occasion, graduate students are paired with a faculty member for a course that is half pedagogical and half content-based. The student is part of the professor’s undergraduate course, preparing for class each day as if he or she will be leading the lecture. Two or three times each semester, the Ph.D. student will actually teach the session. They also write graduate-level papers on the topic of the course, hold office hours, and help undergraduates with research and papers outside of class.

The response to the experiment has been extremely positive, Jáuregui said, with undergraduates praising the process in course reviews and even nominating the Ph.D. students for University teaching awards — resulting in Santiago Quintero receiving a 2017 Kaneb Center Outstanding Graduate Student Teaching Award and Paola Uparella Reyes winning the 2017 Graduate Student Union Outstanding Graduate Instructor Award.

“We want to produce great scholars and great teachers, and we have to prepare them from day one,” he said. “We want them to be successful and give glory to this University with their publications and their success. And we won’t lose track of that goal.”

First year, first graduate

Pietro Bocchia

Pietro Bocchia

It’s rare that a Ph.D. program graduates a student during its first year of existence.

But the Italian program handed out its first degree this year to Pietro Bocchia, a native of Milan, Italy, who transferred from Notre Dame’s Ph.D. in Literature program.

Bocchia’s research focuses on the 20th-century poet, novelist, and film director Pier Paolo Pasolini and his religious theory of knowledge central to his work in the late 1960s. His dissertation also examines the influence of American culture — especially the civil rights movement — on Pasolini’s work.

Bocchia traveled to Italy four times over spring and summer breaks with funding from the Institute for Scholarship in the Liberal Arts and the Nanovic Institute for European Studies. He conducted archival research in Florence, Rome, and Bologna — and visited Pasolini’s only surviving heir, who allowed him to consult the author’s personal library.

Since he completed his Ph.D. in five years, Bocchia received a 5+1 Fellowship to spend a year focusing on transforming his dissertation into a monograph, the job application process and presenting research at three conferences in Italy and the United States. He is also teaching a spring semester undergraduate course called Reconnecting with the Other: Literature as an Antidote to Individualism, which will include work by American and Italian authors.

Though Bocchia came to Notre Dame because he wanted to follow in the footsteps of the renowned Dante scholars here, he shifted his focus after taking a course on Pasolini with Baranski. Bocchia published an article based on the final paper he wrote for the class, then immediately began considering writing his dissertation on his fellow countryman.

“Engaging with Pasolini has been a life-changing experience. I’m really grateful for the opportunity to discover a new world in my own culture thanks to this University,” he said.

Originally published by at al.nd.edu on September 21, 2017.