Antonio Medina-Rivera

Antonio Medina-Rivera

Antonio Medina-Rivera is professor of Spanish and chairperson of the Department of World Languages, Literatures, and Cultures at Cleveland State University. He received funding from the Cushwa Center in 2018 to visit the Notre Dame Archives for the papers of San Antonio Archbishop Robert Emmet Lucey, as well as materials relevant to Archbishop Patricio Flores and the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB).

Medina-Rivera specializes in sociolinguistics and cultural studies. His current research examines Hispanic socialization and leadership among U.S. Catholics from a linguistic perspective. His book project will use archival sources to trace the unofficial policies that have formed Spanish language usage in the Church in the United States since the mid-20th century. Cushwa Center postdoctoral research associate Peter Cajka interviewed Medina-Rivera earlier this summer about his research.

PC: How do the sources you’ve found in the Notre Dame Archives help to illuminate the politics of language in U.S. Catholicism?

AMR: It is more accurate to use the term “language policies” instead of “politics of language.” I believe that the official letters and other documents I found in the archives will help me to understand more clearly language usage (Spanish in this case) among different people in the Church. The documents helped me to identify “indirect” language policies, as well as genuine interest for language maintenance in the United States.

PC: You locate your work in the theoretical framework of language planning or language maintenance. Tell us about your theoretical frameworks and how they help you to interpret primary sources.

AMR: Within the framework of language maintenance and language planning, some of the important factors to consider include the efforts of an institution to give vitality and strength to the language, the creation of new vocabulary, and the ability to give identity and prominence to the language or dialect in use. There are several documents that helped me to identify and understand the effort of some church leaders to develop materials written in Spanish within the U.S. context, the need to train church leaders in Spanish, and the importance of having a better understanding of the Hispanic cultures.

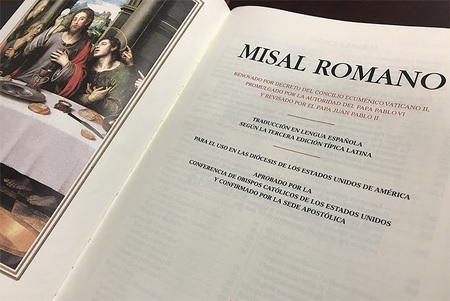

In May 2018, the USCCB approved the first Spanish Missal specifically for use in the United States. Previously, Spanish Masses celebrated in the United States used the edition of the Misal published by the Mexican bishops’ conference.

In May 2018, the USCCB approved the first Spanish Missal specifically for use in the United States. Previously, Spanish Masses celebrated in the United States used the edition of the Misal published by the Mexican bishops’ conference.

PC: When your work tells the story of how Spanish became one of the official languages of the U.S. Catholic liturgy, how does it change or challenge our prevailing narratives of U.S. Catholic history?

AMR: The fact that Spanish is an official language within the U.S. liturgy helps us to have a better understanding of the importance of language diversity and ethnic diversity. Since Hispanics are more than 40 percent of the Catholics in the United States, it is important to challenge the idea of “one Church, one language” or “one Church, one liturgical model,” and embrace the idea of diversity within the Church. The history of U.S. Catholicism has an important Hispanic dimension that needs to be acknowledged—a dimension that is present since the 16th century in the relevant territories. We need to go beyond assimilation and create a better space for Hispanics within the U.S. Catholic Church.

PC: You draw a distinction between direct and indirect policies regarding language. What’s the difference?

AMR: Direct language policies are the ones established in writing or in an “official” way by an institution. Indirect language policies, on the other hand, are common practices within an institution that have never been formalized, but that affect language use in one way or another.

PC: How does Archbishop Lucey fit into your story?

AMR: As bishop of Amarillo and then archbishop of San Antonio, Lucey was in many ways one the pioneers of Hispanic ministry in the United States. During his years he worked very hard to improve services for Hispanic Catholics, he advocated for the creation of the Secretariat for Hispanic Affairs within the USCCB, and for the opening of many Hispanic ministry offices in many dioceses of the country. He was not only interested in the participation of Hispanics in the Church, he went beyond that by advocating for social justice and equal treatment for Hispanics in the United States.

La Biblia Católica para Jóvenes

La Biblia Católica para Jóvenes

PC: What role do the Knights of Columbus play in the process you’re studying? How does your project change our image of the Knights of Columbus?

AMR: One of the Knights of Columbus chapters in El Paso, Texas, was highly involved in the process of accepting vernacular languages in the liturgy, and they directly advocated to include Spanish within the U.S. context. This helped me to see the organization as one that is genuinely interested in the growth and development of Hispanics in the United States. Before, I assumed the Knights of Columbus was just a social club for Catholic males! More recently, they contributed to financing the Biblia Católica para Jóvenes (the first Bible produced in Spanish for U.S. Hispanic Catholics) in partnership with Fe y Vida.

PC: Tell us about your favorite source that you found in the archives.

AMR: I definitely enjoyed looking through the PADRES collection. I was glad to see a group of priests who worked so hard to improve the lives of Hispanics in many ways. The PADRES represented a face of the Catholic Church that was and is involved with the needs of people. My favorite source was letters mixing Spanish and English, which is a clear representation of U.S. Spanish and the bicultural reality of our people.

Originally published by at cushwa.nd.edu on August 14, 2018.