Notre Dame is a Potawatomi place.

When Father Edward Sorin, CSC, arrived in 1842, he found not a landscape devoid of civilization but a civilized place in flux. As the Potawatomi culture fought to maintain its place in the region and European settlers began to establish a foothold on the land, the area was on the precipice of change.

The Potawatomi, who had largely controlled the land since the 1600s, were wealthy and powerful in their own right. Not in the contemporary Western sense, but in the sense that the people’s lifestyle satisfied their needs before European encroachment into their lands. They grew corn, beans, squash, peas, melons and tobacco, and harvested wild rice, berries, nuts and maple syrup, preserving their goods in birch-bark containers.

The History Museum

The History Museum

When French explorers and trappers began regularly traversing the Great Lakes region in the 18th century, tribal leaders met with these European envoys but did not defer to them. As historian and tribal member John N. Low says, they made deals that “operated on Potawatomi terms.”

The arrival of more European groups and the British victory in the French and Indian War, which was waged from 1754 to 1763, meant the Potawatomi had more interactions with the British and their profit-driven economies. This brought greater competition for the region’s resources. Animal furs and agriculture products took on increased value, reshaping some farming, hunting and social practices, and increasing the prevalence of a cash economy. And despite the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which supposedly protected the original inhabitants’ rights to the lands, colonists continued to settle west of the Appalachians.

In the ensuing years the Potawatomi, like all native peoples in the era, worked to negotiate the best deals for their people in light of the changing political circumstances. In so doing, there were Potawatomi who sided with the British during the American Revolution and the War of 1812, both of which led to citizens of the new United States calling for the removal of the Potawatomi from their ancestral homelands throughout the Great Lakes region. For the Potawatomi this happened in large part because of the August of 1812 Chicago-area Battle of Fort Dearborn, where the native people were triumphant but paid a steep price in the public mind for their military victory.

In the aftermath of the battle, newspapers called it a massacre by “Indians,” advancing the idea that native people were dangerous and should be removed. According to Low, 19th-century advocate Simon Pokagon protested the biased language and racially tinged reporting by saying in the Chicago Daily Tribune, “[W]hen whites are killed, it is a massacre, but when Indians are killed, it is a fight.”

- God, Country, Notre Dame et cetera

- 175 and Counting

- En Route

- The Passing of Ancestral Lands

- The Stationmaster

- The Littlest Domers

- The original home-grown do-it-yourself meal plan

- Gettysburg, 1863

- Washington Hall

- Commencements through history

- Cartier Athletic Field

- The old ND&W

- As ND as football, Mother’s Day and community service

- Notre Dame vs. Army: The rivalry that shaped college football

- Bound volumes, illicit lit

- Mock political conventions

- The Collegiate Jazz Festival

- When the Irish got their fight back

- The damnedest experience we ever had

- 40291

- It takes a University Village

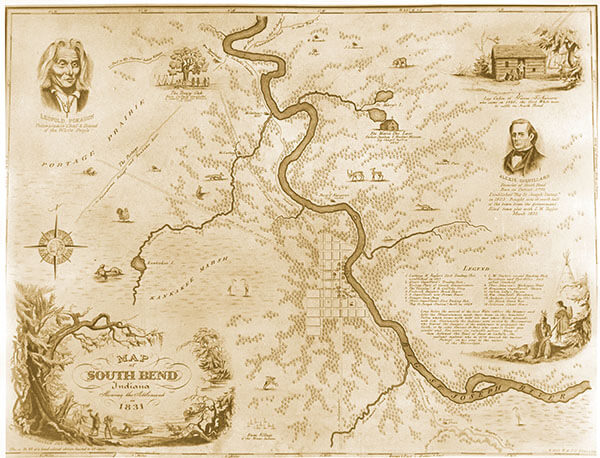

Those attitudes prevailed, leading to dire consequences for Potawatomi and other native peoples. Coerced by governmental action and the threat of removal from their ancestral region, they ceded more and more of their lands in numerous agreements with states, particularly with Michigan. When many native peoples were being forced west of the Mississippi River as part of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, Leopold Pokagon negotiated on behalf of his band of Potawatomi to stay in the region. One of the reasons he was successful was that many Potawatomi people in Pokagon’s band had adopted the Catholic faith. Through their connection to the Church, some of the Potawatomi were allowed (relatively) safe harbor on their ancestral lands.

Pokagon had visited Father Gabriel Richard in Detroit and said, “I implore you to send us a priest.” The priest eventually sent to them was Father Stephen Theodore Badin.

The Potawatomi land of northern Indiana that included what would become Notre Dame already was a Catholic place. Early European settlers knew it as Sainte-Marie-des-Lacs. According to the historian Father Arthur Hope, CSC, the land had been an outpost for the Catholic faith for a long time prior to Badin’s arrival. Hope writes, “The woods had echoed to the ‘Ave Maria’ sung in more than one tribal tongue. Here, at Ste.-Marie-des-Lacs, scores . . . had been baptized. Here, in the rude cabin shelter, Mass had been offered.”

It was in this holy area that Badin built a chapel, near where its replica stands today, known simply on the Notre Dame campus as the Log Chapel. Inside the chapel, a mural depicts the long history of native people and Catholicism on this land. The mural shows native people listening attentively, but the image belies the active role they played in developing their faith, even in the absence of clerical guidance. It was they who practiced the faith at Sainte-Marie-des-Lacs and, through Pokagon’s request, brought missionaries back to this place.

In the 1840s Leopold Pokagon and his community maintained strong ties with the Church’s leaders on the American frontier. Pokagon’s band of Potawatomi even ceded to the bishop of Detroit land and a church that they helped build in nearby Niles, Michigan.

It was that association with Church officials that inspired Badin to argue for Pokagon’s Band of Potawatomi not to be forcibly removed in what has come to be known as the “Trail of Death.” Not being removed in the 1830s and 1840s meant that Pokagon’s people persisted in the region as Sorin arrived in what would become South Bend, where he found the land as the Potawatomi would have regularly seen it, writing to Father Basil Moreau, “Everything was frozen, yet it all appeared so beautiful.”

Sorin was not regularly jaunty in his demeanor or his writings, but he writes that Notre Dame “cannot fail to succeed, even if it receives only a little help from our friends . . . because, in the whole United States, it is evidently the one college whose locations offers it most chances of success.”

Those who have spent winters in Northern Indiana might question Sorin’s optimism, but consider his words as a reflection of the inspiration he drew from the Potawatomi people. He found among his new neighbors food stores for the winter that contained not just nutrition but also centuries of wisdom in making productive use of what the land offered. He heard the echoes of Christian hymns and ancestral songs. He saw the impact of the long history of missionary collaborations with the Potawatomi.

Against that backdrop, Sorin began to build the golden vision of hope for his new school.

Historian Brian Collier, the coordinator of supervision and instruction at Notre Dame’s Institute for Educational Initiatives, regularly teaches Native American history.

Originally published by at magazine.nd.edu on July 05, 2017.