When the University of Notre Dame breaks ground on a new solar project later this year, it will be a full-circle moment for Patrick Regan, whose company, Crossroads Solar, is supplying the panels for the project — and helping formerly incarcerated men and women transition from prison to employment in the process.

A former professor of political science and peace studies, Regan spent seven years at Notre Dame before leaving to start Crossroads with Marty Whalen, a Notre Dame alumnus and former career program manager in the College of Arts and Letters.

Based in South Bend, Crossroads provides jobs and life skills to formerly incarcerated individuals, both men and women, as part of its commitment to “people,” “planet” and “more than profit” — a twist on the traditional “three Ps” of corporate social responsibility.

In starting the business, Regan was inspired by two distinct experiences: working with incarcerated men as part of the Moreau College Initiative (MCI), and researching climate change in his former role as director of the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative, an index that ranks countries based on their vulnerability to and readiness for climate change as part of the Environmental Change Initiative.

Established in 2013, MCI is a collaboration between Notre Dame and Holy Cross College — with support from the Indiana Department of Correction and Bard Prison Initiative — that seeks to ensure incarcerated men in Indiana have access to a world-class liberal arts education. Part of the Notre Dame Center for Social Concerns’ newly formed Programs for Education in Prison (ND-PEP), it draws men from across the state, allowing them to attend college while incarcerated and earn a bachelor’s and/or associate degree from Holy Cross.

On the faculty side, the initiative draws from both Holy Cross and Notre Dame. That includes Whalen from 2016 to 2020 and Regan from 2014 to present. Whalen got involved because of a friend, a former Notre Dame classmate, who spent time in prison.

“It’s huge, to be truthful. It’s validating for us,” Regan said of working with Notre Dame, where he was a tenured member of the faculty and an internationally recognized expert in the areas of international relations, conflict management and the politics of climate change before retirement. “Notre Dame is an institution I used to work for and liked, and it did the right thing and that’s huge.”

By “the right thing” he means supporting formerly incarcerated men and women along the path to re-entry — men and women like Noel Townsend, whose path to Crossroads originated with MCI.

“If you think about the University and its mission, it’s education, of course, but it’s also, ‘How do we promote the common good?’ And this falls in line with that.”

Today, the former Riley High School student is the operations manager for Crossroads, responsible for profit and loss, design, quality control, supply chain management, shipping, receiving, maintenance and marketing.

He dreams of one day leading the enterprise.

“I definitely see the opportunity,” Townsend said, crediting Regan and Whalen for believing in him and his ability to serve in a leadership role within the company despite his background.

A common good

For Notre Dame, the project aligns with both the University’s newly adopted strategic framework, which calls for continued investment in South Bend and the surrounding community, and its Catholic values, which place human dignity at the center of a just and moral society.

At the same time, it’s another step for the University along the path to carbon neutrality, a publicly stated goal by 2050.

Paul Kempf is the University’s assistant vice president for utilities and maintenance.

“It’s a great opportunity and a nice marriage” between Notre Dame and Crossroads, Kempf said of the project. “If you think about the University and its mission, it’s education, of course, but it’s also, ‘How do we promote the common good?’ And this falls in line with that.”

The project, comprising 2,316 panels, will generate about 1 megawatt of electricity, or enough to power about 750 homes. The panels will sit on what is now vacant land north of WNDU studios on Indiana 933. As a clean, renewable source of energy, the panels will reduce campus greenhouse gas emissions by 600 to 700 tons annually, the equivalent of removing as many as 137 passenger vehicles from the road.

Power from the project will flow directly to campus.

Notre Dame chose Crossroads at the recommendation of other local solar companies and after touring the company’s facilities on the city’s far northwest side. KFI, the project engineer, evaluated the manufacturing and quality control processes there and issued its official stamp of approval.

According to Kempf, Crossroads’ values aligning so closely with Notre Dame’s worked in the company’s favor, even as it was unable to match some of its more established competitors on price.

“We have people who have been in prison for 25 or 30 years; a couple went to prison out of high school,” Regan said. “So they have no employment history, no training. But we bring them in and train them and say, ‘Here’s an opportunity for you.’”

For Whalen, those values are what drew him to Notre Dame as a young man — and what lured him back to the University as an adult. A 1982 graduate in sociology, Whalen was among the first cohort of Inspired Leadership Initiative fellows in 2018-19. The program, which is offered through the Office of the Provost, helps professionals, many recently retired, “discover, discern and design” their next act.

“The overwhelming thing I feel is pride in my alma mater, pride that Notre Dame is walking the walk,” the former business owner said. “Notre Dame had an opportunity to make a difference (with Crossroads) and took it.”

Work on the project is expected to get underway later this spring or early summer. The panels are finished, stacked and ready for delivery in a storage area at Crossroads. The University already maintains one solar farm, a 145-kilowatt array next to its Kenmore Street Warehouse in South Bend. Coincidentally, that array sits directly behind Crossroads. The University is also a partner with Indiana Michigan Power in the St. Joseph Solar Farm, a 20-megawatt solar facility in nearby Granger, about 7 miles west of campus. Completed in 2021, the 58,000-panel project sits on land formerly owned and farmed by the Brothers of Holy Cross to feed students at Notre Dame.

But this project is unique in its combination of both environmental and social benefits.

“It’s Laudato Si’ in action,” Regan said, referring to Pope Francis’ encyclical on climate change, which frames climate change as a symptom of a larger problem — specifically, a “throwaway culture” that treats the poor and outcast as waste to be discarded and discounts the value of labor as a source of dignity and a tool for personal growth.

‘An opportunity’

MCI is located at Westville Correctional Facility in northwest Indiana, which is where Regan first became aware of the significance of job discrimination as a barrier to re-entry for former offenders — along with access to housing, health care and other critical supports and services.

As he recalled, he was in class, talking about the value of a college education in the job market, when a student interjected. “But professor,” the man said, “your people won’t hire us, your people on the outside.” That got Regan thinking.

“And I said, ‘Oh, I bet I can do something about that,’” he said.

He looked into logistics, but the work — picking and packing, mostly — was too low-skill for what he wanted to accomplish. Wind was too capital intensive. He finally settled on solar as an ideal space to invest and grow, with the aim of supporting former offenders along the path to re-entry. It helped that he had experience in the climate space from his time at Notre Dame.

Still, he started small. He purchased materials online and built two solar panels by hand in his basement, soldering the cells one by one. From there, he developed a business plan. He also started looking for help with the hiring process. As it turned out, Whalen was leading an internship program for MCI students at the time. The two met. Whalen suggested a broad-based approach to hiring, targeting MCI graduates as well as other former offenders. He also offered to invest in the business. Today, he is vice president, in charge of vision and strategy.

It was a key moment for Regan, who lacked the capital to start the business on his own.

“To be truthful, I didn’t have the money to start this thing,” Regan said. “I had an idea, but I didn’t have enough money that wasn’t retirement money, and I promised my wife I wouldn’t bankrupt us.”

"The importance of Crossroads providing these opportunities and serving as an example to the wider business community cannot be overstated.”

It was fortuitous for Whalen as well. He had been looking for a way to help former offenders based on his experience with MCI. Now he had one.

“When men would graduate from the MCI program, I followed a lot of them,” he said, “and I realized that, even with a college degree, life was very difficult for them. People wouldn’t hire them. There’s a stigma attached to them. And this is after I taught them and realized they were really good human beings who just made a mistake.”

According to David Phillips, research professor of economics at the Wilson Sheehan Lab For Economic Opportunities at Notre Dame, people returning to the community from incarceration face many barriers.

For example, Phillips said, “Sometimes public assistance programs exclude them categorically, and some professions bar people based on criminal record. The same social network that a person might use for support during a tough time like transitioning from prison might be the same social network that’s connected to prior illegal activity. Landlords and employers use record checks, which makes it harder to get housing and employment.”

Overcoming these barriers is not easy, he said.

Crossroads currently employs about 18 people, including three MCI graduates. All are former offenders, both men and women. That number is expected to grow over the coming year as supply chains rebalance and work ramps up on other projects, Regan said.

“We have people who have been in prison for 25 or 30 years; a couple went to prison out of high school,” Regan said. “So they have no employment history, no training. But we bring them in and train them and say, ‘Here’s an opportunity for you.’”

According to Mike Hebbeler, program director for the Center for Social Concerns and managing director of ND-PEP, “Like college on the main campus, we provide MCI students with career guidance to discern and pursue their vocation while cultivating networks of employers on the outside essential for graduates to flourish. The importance of Crossroads providing these opportunities and serving as an example to the wider business community cannot be overstated.”

In Indiana, at least, men and women who leave prison return to incarceration within three years at a rate of about 30 percent, according to the Department of Correction, either because of a new conviction or a violation of post-release supervision. Men are more likely to return than women. The same is true for younger offenders compared with older offenders.

That said, offenders who participate in a work release program are about half as likely to return to prison as those who do not — demonstrating the value of employment as a scaffold to re-entry.

"We’re human beings. We have paid our debts to society; the judicial system has agreed that we have paid our debt to society and released us. Not that you shouldn’t look at people’s past, but you also just have to give people a chance.”

“Good jobs matter a lot,” Phillips said. “One way to see this is to look at the job market when someone gets released. Some people are more lucky than others and get released during an economic boom; others get released during a recession. There are good studies showing that recidivism falls when people get released during moments when wage rates are rising or construction and manufacturing jobs are plentiful. Similarly, recidivism falls when states hike their minimum wage.”

That said, “the ‘good’ in ‘good job’ matters a lot. There are many examples of lighter-touch job search or training programs for people exiting prison that do not improve labor market outcomes,” Phillips said. “My sense of these programs is that people face so many barriers that we should not expect connecting someone to a dead-end job or a week of interview prep to do much.”

‘It’s bigger than me’

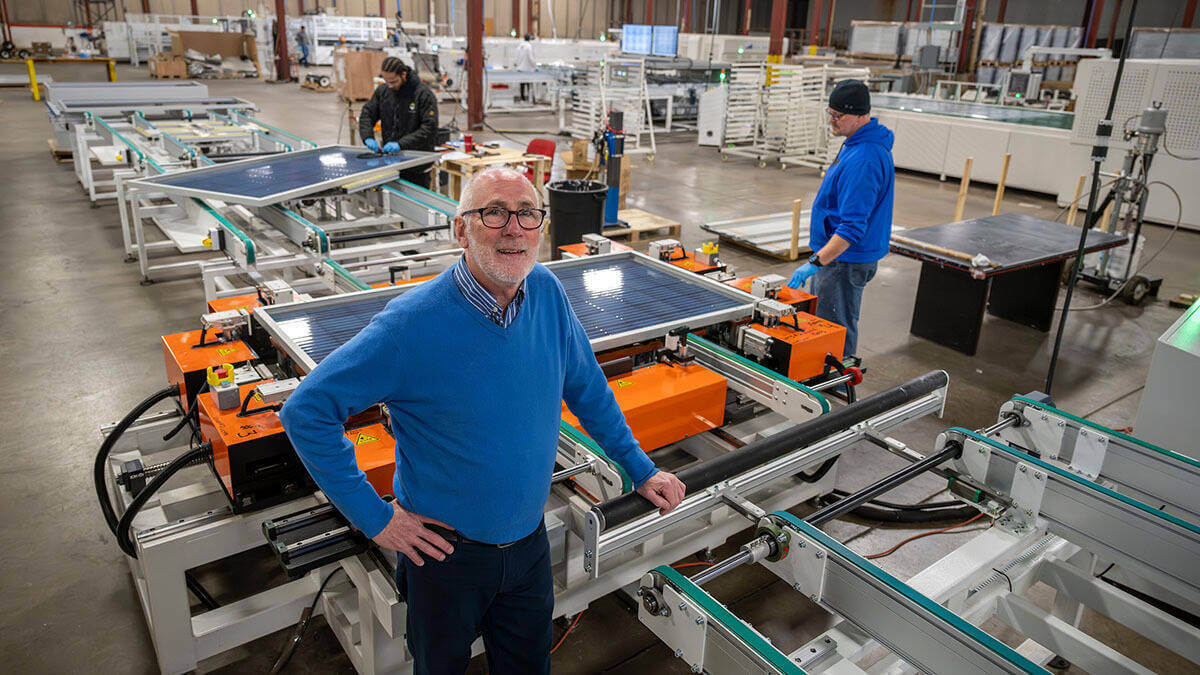

Crossroads leases about 50,000 square feet of space near the airport in South Bend — part of a larger, 150,000-square-foot building along Bendix Drive. It outgrew its original location, a former uniform factory downtown.

Inside, a state-of-the-art assembly line churns out hundreds of solar panels daily. The panels start off as large sheets of glass. A machine arranges pre-manufactured solar cells atop the glass. Workers wire the cells together and then send the panels along to be laminated. Finally, workers attach metal frames and external wiring to the panels and pack them for delivery.

Townsend, the operations manager, oversees it all from a small, wood-paneled office on the plant floor.

Needless to say, he brings a unique perspective to the job.

“Noel manages with grace,” Whalen said. “And I think that until you have been in the shoes of somebody who’s been incarcerated, you may not have the same level of grace that Noel has. That’s not to say that he doesn’t run a tight ship and hold people accountable, but he understands people are human and trying to do a good job, and that the nature of humanity is that sometimes we don’t measure up.”

Townsend knows about not measuring up.

A South Bend native, he was working as a quality control manager for a local RV company in 2010 when he was convicted of a felony drug offense and sentenced to 26 years in prison. It was his first offense, but because he was dealing and because the amount was more than 10 grams, the judge came down hard.

“I attribute it to just greed, maybe stupidity, immaturity,” Townsend said. “Just making bad decisions.”

With time off for good behavior, he spent nine years behind bars. Along the way, he enrolled in MCI and earned an associate degree to go with his two existing degrees: a bachelor’s in engineering from Purdue University and a master’s in business administration from Indiana University South Bend. Regan was one of his teachers.

A free man, he spent the next two years as a quality control engineer and then production manager for a local manufacturer — until Regan and Whalen lured him away to Crossroads.

That was in 2021.

“Career-wise, it’s been great,” Townsend said of the move.

He said he was attracted to the job by Regan and Whalen, of course, but also by the opportunity to improve the lives of former offenders like himself.

“What I experienced at the MCI program, and in prison in general through other programs, was that it’s bigger than me,” he said. “There are men and women out there that are coming home and struggling. It’s hard to find a job. The average non-felon has to knock on 10 doors before they get a job. A felon has to knock on 100 doors before we get a job that’s of the same level. So it’s challenging, and Crossroads helps fill the gap.”

Ultimately, he said, it’s about second chances.

“We’re human beings. We have paid our debts to society; the judicial system has agreed that we have paid our debt to society and released us. Not that you shouldn’t look at people’s past, but you also just have to give people a chance.”

Originally published by at news.nd.edu on February 15, 2024.